Exploring circularity: Europengineers on Piano.

ROD's Laura Fernandez and Kieran O'Riordan describe what they learned in an impactful circularity in construction workshop organised by Europengineers

Last February, we attended a design sprint on the theme of circularity in construction in Paris. The three-day event was organised by Europengineers and hosted by Setec, one of France’s largest engineering consultancies. It was attended by representatives from several Europengineers member companies, including Basler & Hofmann, Buro Happold, Hydea, Aronsohn Consulting Engineers, Schüßler-Plan and Salfo.

The design sprint focused on the opportunity to reduce the embodied carbon, energy and raw materials within buildings generally and on reusing existing materials and components in new buildings in particular.

In a linear economy, raw materials are extracted from the earth, used and discarded: “take-make-waste”. At best, this economy leads to the relative decoupling of economic growth from the use of natural resources. In the reuse economy, many non-recyclable materials are used again (cascading, repair/maintenance, reuse, remanufacturing). In the circular economy, raw materials are never depleted. This economy can be structured so that there is a positive coupling between economic growth and the growth of natural resources (”negative” emissions/positive footprints).

While the construction industry is responsible for significant raw material and energy consumption and carbon production, there is growing awareness of the need to make current industry practices more sustainable to avoid depleting or exhausting our finite resources. Ireland, for example, has introduced the BER (Building Energy Rating) certificate and NZEB (Nearly Zero Energy Building) directive to reduce the net energy use of buildings during their operational phase. Parts of the supply chain have also responded by taking steps to improve their operational processes in terms of sustainability and energy reduction. ROD has, for example, an NSAI accredited ISO 14001 Environmental Management System.

During the workshop, we were presented with a case study of Renzo Piano’s Thomson factory in Guyancourt, which was scheduled for demolition. After being split into groups, we were asked to come up with ideas on what could be made of the extracted components of the building, a task that was made easier because of its distinctive steel-framed modular arrangement. The more modest ideas included a low technology community building and a marketplace while the more ambitious included a modular metro station and an Olympic stadium!

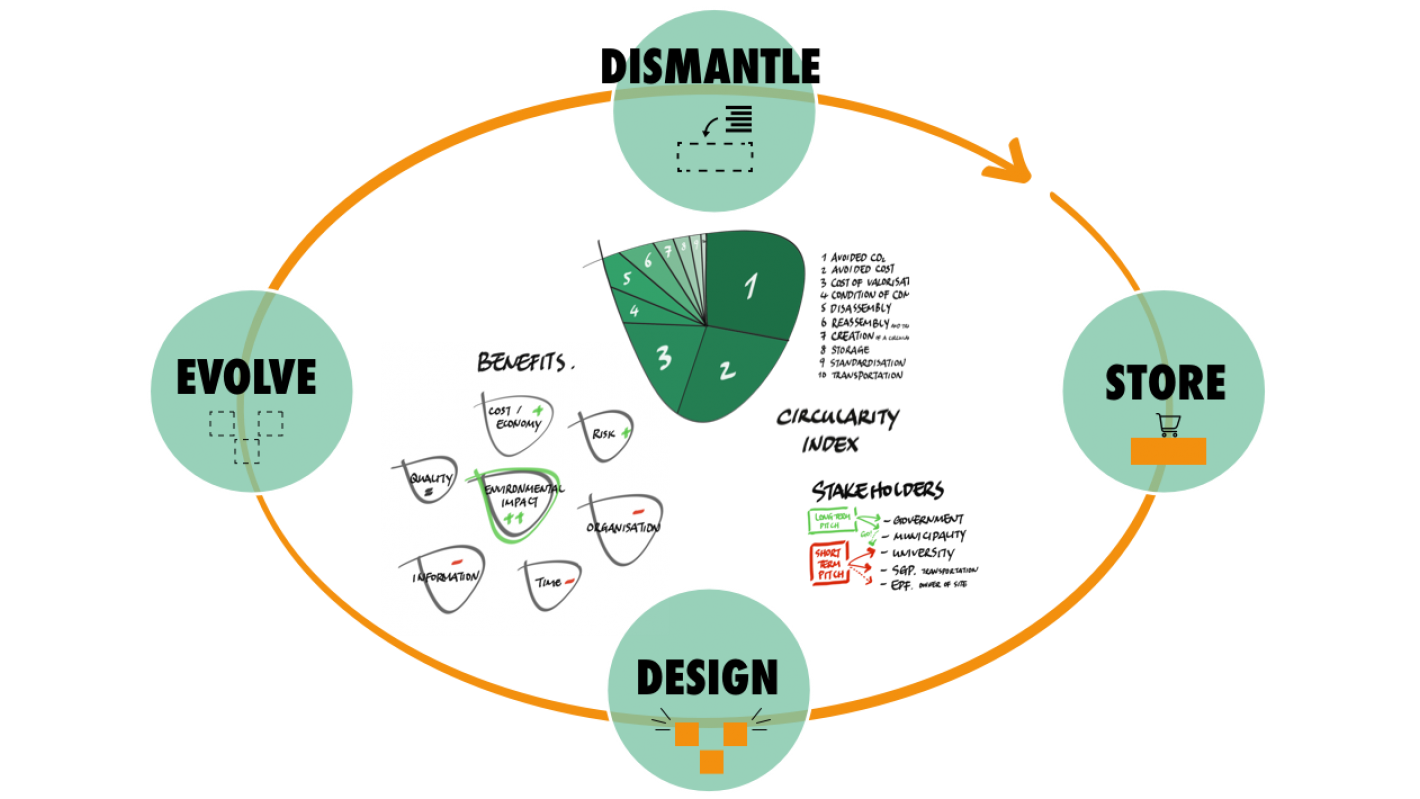

After choosing the best idea from those presented, we worked together to develop concepts relating to:

The workshop underscored for us the importance of thinking about reuse and disassembly when designing new buildings. Key considerations at the design stage should include standardisation of structural member sizes and lengths, repetition of structural arrangement (modularity), the type of connections (welded vs. bolted) and potential future use (versatility). It also helped us appreciate that defining a building’s circularity index is complicated by the many quantitative and qualitative factors influencing it, including:

During the workshop, we had to consider the best approach to reusing materials and components. One approach is to completely dismantle the component, for example, breaking up concrete or melting steel to be treated and transformed into a new component. This type of material is frequently used and comes with a ‘material passport’ that allows the sustainability of the material to be identified. Some characteristics of this approach negatively impact the life cycle index however.

Another approach is to reuse the original component, keeping its original shape and avoiding a manufacturing process. We imagined an open source digital library of reused products and components that is integrated in the Building Information Modelling (BIM) process so it can be accessed in both modelling and analysis software during the design stage. Each component will contain a series of parameters forming its ‘digital passport’, allowing designers to make informed decisions in terms of circularity while also keeping the raw materials used in its construction in a ‘closed loop’.

Will we ever reach a stage where designs are driven by the availability of existing, reusable components? The question remains to be answered.

We used the process followed for the Thomson factory to derive a methodology to evaluate circularity on other projects. It is hoped that this methodology can gain widespread acceptance in the construction sector and, as a result, become more attractive to clients.

From a personal perspective, it was interesting to see how awareness of circularity is increasing in other European countries and to expand our network of contacts outside Ireland. Who knows when the opportunity to collaborate on future projects or share technical knowledge may present itself!